Quitting a job often can be a good thing. But not enough workers have been doing it.

During and after the recession, the U.S. economy has been too weak for many workers to undertake the sort of job-hopping that economists say is critical to building careers and advancing the nation’s long-run growth prospects. The consequence: Even many Americans who have remained employed have stunted their earnings growth by staying pinned down to their current jobs.

The weak job churn is among Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen‘s leading concerns about an economy that is improving steadily, but with substantial scars just beneath the surface.

WSJ Economics Chief Neil King explains the state of the American economy. A new report found an increase in employees jumping around in the job market, a sign of increased confidence in hiring. However, outlook for the economic future in U.S. is still uncertain.

Ms. Yellen, who is set to deliver the Fed’s semiannual report to Congress on Tuesday and Wednesday, regularly highlights her concerns about the lack of dynamism in the labor market. “People are reluctant to risk leaving their jobs because they worry that it will be hard to find another,” she said earlier this year.

One such person is David Clark, a 31-year-old in Atlanta who said he never planned to spend most of his 20s in the same ad-agency job.

“For a while I closed my eyes and stuck my fingers in my ears and hoped I could ride it out at this one place,” Mr. Clark said.

The recession hit two years after Mr. Clark graduated from college, leaving him stuck in a position that offered no opportunities for advancement in an economy that offered little hope of jumping elsewhere. “I became a little emotionally frozen because every time I’d look for jobs there would be nothing,” he said.

By hopping from employer to employer, especially early on, workers find jobs better-suited to their skills, build their résumés, bid up their salaries and boost lifetime earnings prospects. They eventually settle down and change jobs less frequently.

“One of the characteristics that is uniquely American is that changing jobs is the way you get promoted,” said Anthony Carnevale, an economist who directs Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce.

While the nation’s jobless rate dropped to 6.1% in June, the lowest in nearly six years, the improvement masks the fact that many workers who held jobs throughout the downturn and recovery struggled to advance.

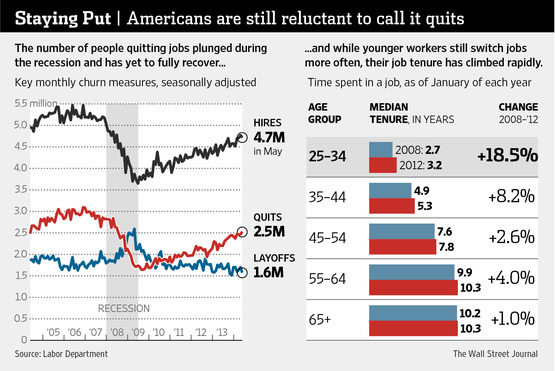

Their plight is best captured by the collapse in the monthly hiring rate, from 5.5 million in 2006 to as low as 3.6 million in 2009, according to the Labor Department. It was 4.7 million in May, the latest figure available.

People leave jobs by two main ways: voluntarily quitting for a better job, which is beneficial, or getting laid off, which is detrimental. In the recession, the rate of career-damaging layoffs spiked. It has since returned to its prerecession levels.

The number of people voluntarily leaving positions fell by nearly half to 1.6 million in 2009 from 3.1 million in 2006. It stood at 2.5 million in May.

As churn slowed, workers began clinging to their jobs. From 2008 to 2012, the most recent year available, the median tenure of workers ages 25-34 in their current job rose by 19% to more than three years. Workers ages 35-44 saw their tenure climb 8% in the same period, to about five years, and those ages 45-54 saw their tenures climb by 3% to eight years.

Job tenures are longer in other industrialized economies, economists say. Direct comparisons aren’t available, but in most developed countries average job tenure is more than a decade, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a group of 34 mostly advanced nations.

Without more frequent switching, fewer U.S. workers are finding the jobs and wages that suit their skills. As much as 66% of lifetime wage growth occurs in the first decade of a person’s career, according to one widely cited estimate first by economists Robert Topel and Michael Ward in the late 1980s. Other researchers since then have found similar effects.

Many graduates beginning careers in a recessionary economy end up “two steps back from where they might have been in a full-employment economy,” Mr. Carnevale said. “The evidence says it can damage you for a career.”

To be sure, some workers are starting to break free as the economy heals—offering hope that more careers will get back on track.

Charles Albert was grateful to land a job at Northern Illinois University’s admissions office after he graduated from the school in 2009. He expected it to be a brief stop. Still there two years later, he was “starting to feel the pains of the economy.”

“I was making $25,000 a year in Chicago,” said Mr. Albert, now 26. “That does not go very far.”

After six months of applying for jobs, he made the jump from recruiting students for a school to recruiting for health-care and insurance companies. Over the past two years he made two more jumps, becoming a recruiter for higher-level jobs and bumping up his salary until he became the director of research at Jobplex Inc., a Chicago recruiting firm.

The churning process eventually worked for him, but many of his peers weren’t so lucky. “I have friends who graduated the same year I did who still are working the same job they did right out of undergrad,” Mr. Albert said.

Young workers always have earned less than those with more experience, but the gap has widened. In 2004, the median wage for workers 25-34 years old was 5% lower than the overall median wage. Today, it is 8% lower.

Graduating into a recession can have enduring hit on earnings. Men who graduated in the early 1980s downturn suffered an initial wage loss of 6% to 7% for each percentage-point increase in the national jobless rate, according to research by Yale economist Lisa Kahn.

Even 15 years after graduation, their wages were 2.5% lower than those who didn’t enter the labor market during that downturn, showing how recession scars linger.

So far, the damage to young workers from the most recent recession appears much more severe than in the 1980s, Ms. Kahn’s recent research found.

“I would say everyone is optimistic now, but that doesn’t mean they are not thinking about the recession anymore,” said Tunc Kip, 31, the president of Atlanta’s junior chamber of commerce. “There is still a lot of thought about how things were a couple years ago. It makes people a little more conservative with decisions toward shifting careers.”

Mr. Clark, the young ad man in Atlanta, watched his agency struggle throughout the recession as one of its largest clients, Eastman Kodak Co. KODK +2.52% , entered bankruptcy. He occasionally found himself envious of older relatives and friends who started their working lives well in advance of the recession and “didn’t have the brakes slammed on their careers the same way we did.”

In March 2013, nearly four years after the recession ended, he finally landed a job with a different ad firm in Atlanta, Ogilvy & Mather, and began the long process of catching up.

“I’m happier,” Mr. Clark said. He is earning more money and has some savings, but not enough for a house. For him and his wife, “having a family is not really on the horizon, because we’re not building up the base.”

And “in the back of my mind,” he frequently reminds himself, “it could all fall apart again.”

Write to Josh Zumbrun at josh.zumbrun@wsj.com

Corrections & Amplifications

An earlier version of the chart accompanying this article incorrectly referred to a measure of job tenure as an average. It is a median. (July 14, 2014)